SO EXCITED!!!

Have a good day folks!

-frootza <3

Yoink.

Composer/Scientist

Thomas Edison State University

Earth

Joined on 6/4/09

Posted by frootza - August 31st, 2015

Take a Break

That is my advice, truly. If you are writing non stop, and reach a creative block, it is, in my opinion, your brain's way of telling you to slow down so it can rewire itself.

Go outside, and just ponder music. You will find inspiration in the strangest of places. Quick example...

I was writing some music with my drummer at his place. We took a break to just sit and think. I listened to his fan banging rapidly against his dresser and it had a fast tempo and unique rhythm. So, we decided to run with it and came up with some tasty music.

So, in summary, don't forget to take breaks, you will let your brain refocus when you go to compose again.

Detailed posts arriving shortly, hang tight guys!

<3

Posted by frootza - July 1st, 2015

Composition Advice (#4)

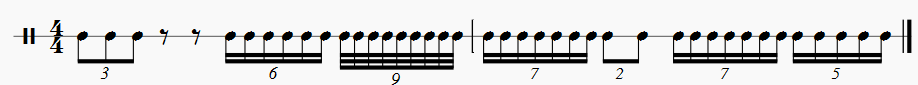

Karnatic Rhythmic Subdivision ***

Karnatic subdivision is a really interesting concept to delve into. I first heard this kind of music when I would listen to artists like Ravi Shankar, and first seen it live when I went to a Diwali festival with an unbelievable Sitar and Tabla player who were writing their own music and playing some classical standards too.

Karnatic Subdivision is found in Classical music in Southern India. What fascinates me about it, well one of the things anyway, is how they can seamlessly transition between these very intricate time changes. I'm going to attempt to explain this as simply as I know how, though I might expand on this later with notation *Yoink, I did, it's at the bottom! *

You can also include KS in Western music! It isn't restricted to that region, and certain artists have began implementing these rhythmic techniques into their playing.

You have probably heard of a triplet, sextupet, nontuplet even. This, in it's most basic sense, is what karnatic subdivision is. In fact, if you look at a Whole Note, you have probably heard a whole note like this. Speaking in 4/4 time.

Whole Note: 4 Beats

Quarter Note Expressed:

1 - 2 - 3 - 4

Simple right? It isn't as hard as you would think, but counting it can get very difficult.

*This simple form of subdivision is referred to as Chatusra*

My point being is that when we begin so subdivide beyond this, it starts to look a little bit different. To elaborate...

Quarter Notes:

1 - 2 - 3 - 4 -

123-123-123-123

This is the basic triplet illustrated textually, where each set of three (123) is linked to 1, 2, 3 and 4 (beats) respectively. *This is known as a Tisra in Karnatic music*

Quarter Notes:

1 - 2 - 3 - 4 -

12345-12345-12345-12345-12345

This would be a quintuplet. Again, the subdivision going to the quarter notes. *This is called the Khanda in Karnatic music.*

*Misra is 7

Sankirna is 9

Tisra second speed is 6

Chatusra is four

Chatusra half speed is 2

Chatusra second speed is 8*

In order to start implementing this into your own musical writing and playing, it might be a good idea to practice counting these subdivisions to a metronome, as slowly as possible at first. The reason being is because you need to be able to feel the subdivisions of the beat, as they aren't going to be handed out to you like they usually are with a metronome or a drummer.

BEYOND the basic subdivision, are the permutations of the beats themselves. By that I mean, you can still count the subdivision, but it doesn't mean that your notes must fall on the subdivision since you can rest, and play with the note order while still subdividing the beat.

I'm not an expert on Karnatic musicby any stretch (yet!), as I've just discovered it recently and have began studying it recently as well. But, I do hope that you found this read interesting and may consider implementing some of these concepts into your own writing as well.

Take care! I'm going to be including a quick illustration of KS at the bottom, or somewhere in this newspost for you guys to peruse. Later I might delve into sequencing KS (which can be tricky), but as I was writing this I thought it would be more useful to explain these concepts first. Enjoy, and if you have any questions don't hesitate to ask. This is not a subject that can be so easily glanced over in my opinion, and takes time to understand and implement into your own playing and writing.

frootza

Pretty cool example of some of this stuff being utilized in a jazz-improvisational format.

Posted by frootza - June 2nd, 2015

Composing Advice #2

Repairs

Beyond the Limitations

In my first news post, I shared a few tips that I've come across in my own study of orchestration in regard to writing parts that can be played by live musicians. If you know have listened to any of my work that has been performed live, you probably know that I write some bizzare and intricate music. I do try to push the boundaries of what I write and push the players that I write for. Sometimes what has been written, even by a world class composer, is just not playable because of minor mistakes, deadlines, or an inexperienced ensemble. The composer's mistakes will have to be fixed by the conductor, or the ensemble itself.

This recently reminded me of a musical term called "scordatura".

"Scordatura, is a tuning of a stringed instrument different from the normal, standard tuning. It typically attempts to allow special effects or unusual chords or timbre, or to make certain passages easier to play."

-Wiki

For guitar, as I'm sure most of you know, it is pretty simple to detune, or use alternate tunings while performing. For other "orchestral" instruments, it isn't quite so simple to do IN practice.

Asking a Violinist to tune their high E string up a whole step is not particularly a good idea. Those things break, and when they break, it isn't as non-chalant as a guitar string break. It's kind of like having your tire 'POP' while on a highway. It's frightening, and it can and will hurt if the string hits the player (especially in the eye!).

What we tend to forget is that these string instruments are quite expensive by comparison to common rock instruments (for a high quality instrument). While talented players are often very familiar with the intricacies of caring for their instrument, less experienced players are commonly not. So, by asking one to detune their entire instrument for a single performance, we will be affecting the said instrument's intonation. In addition, sight reading can become more difficult since the finger positioning gets altered. With it comes many problems that performers would prefer not to deal with and likewise the conductors themselves.

There is most definitely a time and a place for utilizing scordatura in your compositions, but if you are going to do it, make sure that you do so for a composition that is going to make GOOD use of the scordatura.

If you have sparse measures where your Contrabass dips down to a Cb, consider re-arranging these parts. This is a bad useage of scordatura.

If you are utilizing scodratura for effects, or you truly need to have a specific interval or chord played that cannot be performed any other way... then, go for it! Just do a bit of research first into compositions that have utilized it before as a reference point. This, I would consider to be good usage of scordatura.

Repairing your Work

It isn't that difficult to spot the unplayable, but those of us who use step sequencers may come across this problem more often than those who write directly into notation software. Here are a few ideas you might consider to repair your work...

1) Key Change--Up or Down. It is often the most simple to get the parts within range if your part has dipped above or below. Also, the simplest method.

2) Physical edit--Sometimes the part you have doesn't really need to be played as high as you have it. Try another melody that still compliments the other parts you wrote, without taking away from what you want the listener to experience when hearing your work.

3) Revamp--Obviously this method takes the most time, but it is possible indeed. The need for revamps usually will take place between a Violin and Viola part, or a Cello and Contrabass. The confusion of the range of these instruments is where most mistakes come into play. Where it gets tricky is when you need to add an extra musician to accomplish your work. It can be as simple as switching your Viola part to a Violin, or your Cello to a Contrabass etc. You might also consider splitting the voicing for your Celli to pick up the under-range that the Viola can't play. If your work demands the voice to be heard, let it be heard.

4) Split Voicing--In orchestras there is more than one player for a designated instrument (unless you are writing for a small ensemble). If you expect an entire Violin section to bow over three strings with ease, in the same manner you would play a Ukelele, you might be asking for a little too much. Try splitting the part between the 1st and 2nd Violins. Or perhaps you could just be clear in your notation that the passage that is about to be played should be played by multiple players within the section. The first char might take the top note, second chair the middle, and so on. This makes the more difficult passages easier to manage for everyone.

Hopefully this gives you guys something interesting to consider when writing your next composition or reviewing one of your old compositions.

Posted by frootza - May 29th, 2015

Composition Tips #1

Being an Honest Composer

Limitations

All instruments have limits of what can be physically played by musicians in a live setting. I hear quite frequently, compositions which sound great in terms of their actual sound output. But, the music itself is, in reality unplayable by actual musicians. You need to keep in mind what the players can actually play, otherwise you will be trapped within the realm of digital performance which isn't ideal.

Mind you, there is absolutely nothing inherintely wrong with writing like this. Writing from your heart so to speak. Most would encourage you to just write whatever you feel. This too, is great practice. You can write some great music, but it will never be performed live UNLESS you actually learn what can be done.

Why should you even be concerned with the limitations of live performers? Why should you even bother to write for musicians?

The first question:

Musicians spend years harnessing their craft, in the same way you may have spent years harnessing your production and writing skills. It is unprofessional, and to some, almost insulting, to receive a piece designed to be played by one's designated instrument, only to find that the music can't be played. Not because they aren't skilled enough to play the piece, but because the instrument is unable to handle what has been written. Even the most virtuostic of performers have their limits, due largely in part to the instrument's design itself.

The second question:

Digital performances can sound great. They often DO create the illusion of realistic performances. But it feels much more rewarding having your work performed by real people than it does having your work "played back" by a VST. Keep the idea of writing for live performers in mind. It can be done! In doing so, you will increase your chances, greatly, of having that work performed. You may even be asked by an orchestra member who enjoys your piece, if they can purchase your score so that it can be played in front of a live audience, or recorded in a studio by real players.

Examples...

#1) You write a piano composition. You hear the playback, it sounds wonderful. In fact, it is wonderful. You wrote an excellent piece of music! A pianists asks you for the score, and you happily oblige and give it to them. Upon reviewing the score, the pianist realizes that the left hand part features octaves. Playable, of course. But the octave part you've written happens to jump up a seventh. The tempo is too fast, being written at Presto. What happens now? Your work falls under the category of a digital performance.

#2) You've written a brass arrangement. It sounds really great! The band you've worked out a deal with is eager to play the arrangement for a rehearsal. It turns out that your flugelhorn part holds a high C for 10 measures straight at 60 beats per minute. What happens now? There is only one flugelhorn player in the band, and they can't play the high C for ten measures. The composition loses it's playability. Again the works becomes a strict digital performance.

#3) You write a metal song. It's really awesome, and you've air drummed through the parts, and it feels playable for you. The bridge arrives as the drummer is reading through the piece. The bass drum is playing a semi complicated 32nd note pattern. Six measures into the bridge, the drummer's heels tire out, they slow their playing down and lose the tempo. You are upset that the drummer couldn't handle the part you wrote, and you try playing the same part on the drum kit. You realize that you can't even play the same part you wrote at half the tempo. What happens now? Digital performance land.

How to begin applying these ideas to your own work.

1) Have a reference sheet handy which includes the range of the instruments you are writing for. You want to avoid accidentally writing a part which is too high or too low for the instrument to reproduce

2) Ask yourself, occasionally... "How hard will this be to play? What skill level am I writing for? How many musicians would be required to play this?" When it comes to transcribing your score, if you've had these questions in mind, the transcription process will be much smoother.

3) Look at a picture of the instrument you are writing for. Having a handy, clear image of the fretboard or piano can help with writing a more cohesive piece. You may have written a harmony to be played by a single player that needs to be performed by two players separately, or you have have written a piano chord that would require a second player to accomplish.

4) Learn as much as you can about the instruments you are writing for. Watch videos. Go to a rehearsal. See a few shows that feature live players and watch what they are doing closely. The more you learn about each individual instrument, the more effectively you will be able to write for said instruments.

5) Find players, and ask them to review your work. You don't need to have them play the entire piece. But if there is a particular section that you are questioning, then it would be useful to get a second opinion. As you improve, these players just might want to play your music! Which, is of course, one of the primary purposes of me sharing my viewpoint here. :)

Enjoy the journey! More tips to come as I think of new and relevant topics to address that I feel I'm qualified to advise upon.